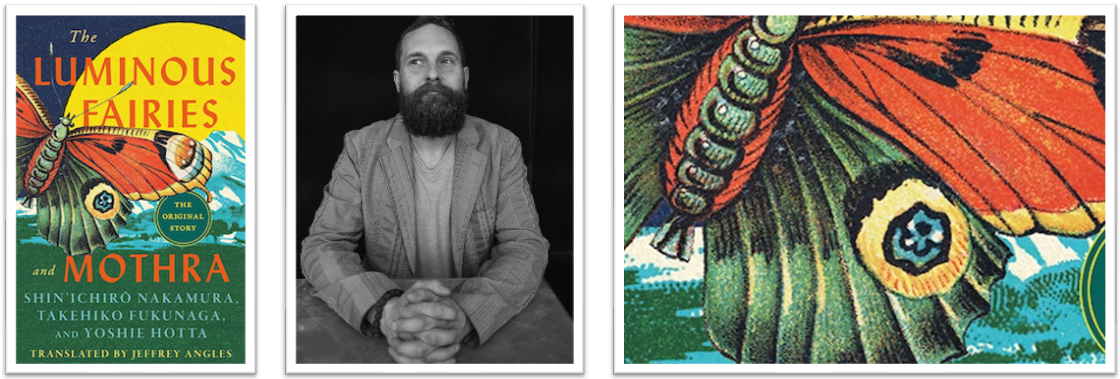

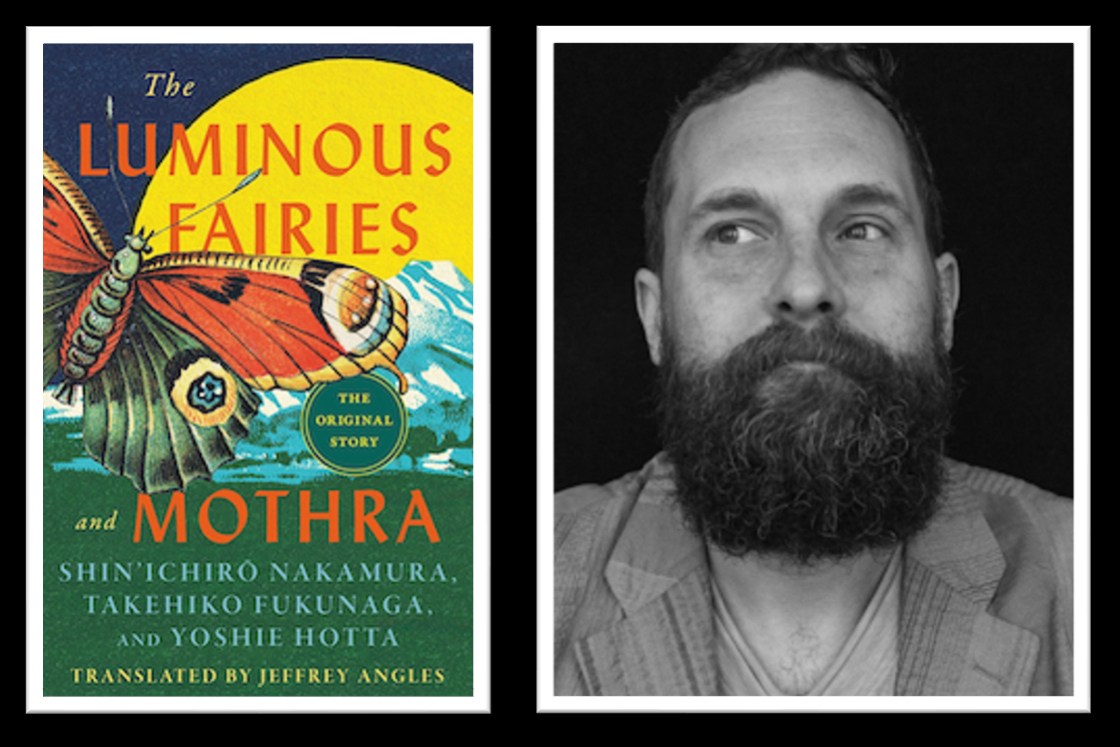

Mothra Q&A: Translator Jeffrey Angles talks making the original kaiju fiction available in English!

“Tōhō’s monster movies are great fun, but they are also fantastically revealing windows into an extraordinary dynamic literary, cinematic, and cultural moment in time.”

Monster Complex® talks with translator Jeffrey Angles about making the original 1960s Mothra fiction available to read in English for the first time in like 60 years!

In the world of giant monsters, one of the best-known kaiju is Mothra. First appearing in Toho’s 1961 Japanese movie Mothra, directed by Ishirō Honda, she has over the years appeared in lots of giant monster movies—including several entries in the Godzilla series.

Generally shown as either a giant moth or a giant caterpillar—and accompanied by two mini fairies who talk for her—Mothra is almost always one of the heroes in the story. For English-speaking fans, we generally only know about Mothra’s origins from the movies. After all, they’ve been shown on TV and other video media for decades.

But in Japan, Mothra actually first appeared in print.

In 1961, when Tōhō Studios was planning to make the original movie that debuted Mothra, they began the process by hiring three prominent Japanese authors—Shin’ichirō Nakamura, Takehiko Fukunaga, and Yoshie Hotta. Those authors wrote the novella The Luminous Fairies and Mothra.

Written just months after the largest political demonstrations Japan had ever seen, The Luminous Fairies and Mothra reflected the rebellious spirit of the time. In the original story, explorers visit a South Pacific island and capture a group of fairies, inciting the fury of the goddess Mothra, who sets out for Japan on a mission of rescue and revenge.

Expressing a powerful social stance—about Japan’s need to chart its own foreign policy during the Cold War—the novella’s political message was ultimately toned down when it was adapted into the Tōhō Studios film.

And in all the years since it was published, the book was never available in English.

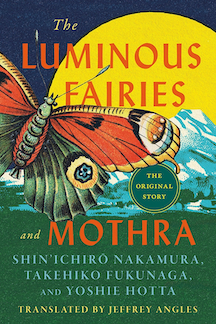

In 2026, The Luminous Fairies and Mothra will finally be available in English.

The book has been translated by Jeffrey Angles, professor of Japanese literature at Western Michigan University. An author himself, he has also translated several works in Japanese—including Godzilla and Godzilla Raids Again.

For The Luminous Fairies and Mothra, Angles also wrote an extensive afterword. He shares about the novella’s cultural context, the unusual story of its composition, and the development of the 1961 film.

In our exclusive interview, Angles talks to Monster Complex® about what led to him translating these Mothra and Godzilla books into English, the process behind the work, and some of the ways the original book was hanged for the first Mothra movie.

Monster Complex® sometimes uses affiliate links. (At no additional charge to you. Relax.)

Buy The Luminous Fairies and Mothra

By Takehiko Fukunaga, Yoshie Hotta and Shin'ichiro Nakamura

Translated by Jeffrey Angles

Bookshop (which also supports your local bookstore!)

Interview: Translator Jeffrey Angles on The Luminous Fairies and Mothra

Note: Angles did a nice interview with Toho Kingdom about his Godzilla translations. (Read that here.) Since that interview covered details about the making the books, my questions are more about his emotional context…

Q: Given your background as a professor and a poet and a scholar—how much of your experience translating the original Godzilla and Mothra works is, well, “scholarly,” and how much with these are you engaging in a kind of fandom that says, “Holy crap, these were the beginnings of Godzilla and Mothra!”

That’s a good question! There is a little bit of both.

When I was little, I loved watching reruns of the dubbed, vintage kaiju films on TV. I remember sometimes stomping on shoeboxes with my friends, as we pretended to be Godzilla ourselves.

As I look back on it now though, I realize that although I enjoyed the monsters, I was just as attracted to the unfamiliar cityscapes and mid-century-modern, pastel interiors of a country that I didn’t get to see until 1987, when I first went to Japan as an exchange student. That was where my origin story as a Japanese literature professor began.

Later, in graduate school, I specialized in Japanese literature. I read a lot of old boy’s adventure fiction, and I even wrote part of my first book, Writing the Love of Boys, about Rampo Edogawa (江戸川乱歩), a key figure in the history of modern detective-adventure fiction.

The idea of studying Godzilla academically didn’t even occur to me just before the pandemic, when I was watching the 1954 Godzilla with a group of students in class.

I noticed that the second title after the title of the movie said, “Based on the work of Shigeru Kayama” (原作 香山滋). I had surely let this credit roll my many times before, never paying much attention, but this time, I found myself surprised.

Kayama had started his career by winning a short story contest sponsored by the magazine The Jewel 『宝石』, founded by Rampo Edogawa, the author whom I’d studied so extensively. For the first time, I realized that there was a direct connection between the kaiju I had enjoyed as a boy and the mid-century Japanese literature I had spent so much time reading.

Q: So, are you a fan of these classic monsters, or is your translating work more about their historical value? (And in case you are a fan—what is your background with these monsters? Your earliest memories of which movies or games or whatever, etc. Are you still a fan of what they are appearing in now?)

I had incorrectly assumed that everything that needed to be said about Godzilla had already been said, but once I realized that there was a literary connection with the kaijuverse that hardly anyone had even bothered to explore, I couldn’t resist. About that time, the pandemic started, and like everyone else, I ended up cooped up at home, bored out of my skull.

That’s when I began thinking about translating Kayama’s novellas Godzilla and Godzilla Raids Again. They’re so good that it struck me as a crime that they hadn’t yet been translated yet. I thought, other fans—not just me—would want them too, wouldn’t they?

Tōhō’s monster movies are great fun, but they are also fantastically revealing windows into an extraordinary dynamic literary, cinematic, and cultural moment in time. When University of Minnesota Press published the Kayama translations, they let me append the long afterword that I had written talking about Kayama, the cultural history that led to the creation of the first Godzilla film, and the sociopolitical anxieties and economic realities that motivated Kayama and the subsequent screenwriters at Toho who adapted his story to the screen.

A number of fans wrote to University of Minnesota Press urging them to publish a translation of The Luminous Fairies and Mothra 『発行要請とモスラ』 next. The press conveyed this to me, and I went to town.

This time was even more fun since there were three authors who cooperated to write The Luminous Fairies and Mothra, and they are all really fascinating figures in literary history. I already liked one of the authors, namely Takehiko Fukunaga 福永武彦 whose book Flowers of Grass 『草の花』had captured me with its dreamy, melancholic prose. This novel is about a bisexual young man and his reflections on art, life, and love before his death from tuberculosis.

The other authors, Shin’ichirō Nakamura 中村真一郎 and Yoshie Hotta 堀田善衛, turned out to be equally, if not even more fascinating. Hotta was especially interesting because he was so involved with politics. As a result, there is a strong political subtext that was removed when the novella was adapted to the screen. I write a lot about that in the scholarly afterword that I appended to the back of the book. There is so much to say about The Luminous Fairies and Mothra that my afterword ended up being much longer than the novella itself!

Q: For the actual translating process itself: When translating these Godzilla and Mothra works, how much of that process for you is simply like, um, math—just a routine—versus you bringing some artistic perspective to make these what they were intended by the authors? What are the challenges for works like these? (As a poet yourself, are you drawing on any of your own artistic perspective for these?)

Well, in doing translation, there is always a little of routine work involved, as well as a little art. I usually start by trying to do a very literal version that transforms or adds as little as humanly possible.

Then, I keep going back over the text repeatedly, ironing out textual issues and making things sound smooth and natural while trying to anticipate spots that might sound funny or be hard to understand.

Of course, I don’t want to overstep my bounds as a translator-scholar, especially since my goal is to give as accurate a picture of the original text as possible. That being said, there are always places where a translator needs to use their imagination to figure out how to solve certain problems in the text itself.

Q: Could you give us an example of the kind of things that a translator might need to decide on their own?

Definitely. In the Japanese language, people tend to use gendered pronouns far, far less than in English. Indicating a character’s gender isn’t required by the language itself, whereas in English, some of the most important pronouns—“he/his” and “she/her”—are explicitly gendered, making it hard to avoid gendered language altogether.

In The Luminous Fairies and Mothra, there are only four places in the story, all concentrated in one spot, that indicate Mothra’s gender. I was gobsmacked to find that there, the original Japanese text used the male pronoun kare (彼 meaning “he/him”), not a female pronoun.

As a translator, I had to think about what to do. Did the original authors think of Mothra as male? However, popular discourse in Japan as well as the English-speaking world has tended to describe Mothra as female. What should I do about that?

However, as I mulled it over, I realized that Mothra is a story about transformation. One of the authors even said in an essay that he wanted to make the kaiju a moth since moths go through so many transformations in their life cycle, and that would make for good on-screen viewing.

Since physical transformation is at the very heart of the story, I realized that perhaps it wasn’t really a problem for me as the translator to use male pronouns where they are found in the text, then follow popular tradition and start using female pronouns when Mothra breaks out of the chrysalis, taking on final form as a colorful moth.

In short, gender could be simply one more way in which Mothra was transforming. In essence, I built upon what small hints were there in the text, reconciling the male pronouns in the text with popular discourse and fandom, which has always treated Mothra as female.

In doing so, Mothra begins to look like a non-binary or transgender kaiju who isn’t necessarily limited by traditional, dichotomous notions of gender. To me that take on Mothra makes a lot of sense.

Q: Since these original works go all the way back to the beginnings of Godzilla and Mothra—how shocking that so many of us English-language readers are only learning about them now! To you, how much of what you’ve been able to do for us is literary or artistic... and how much is this is like you’re a kid who found the best candy and can now introduce it to the rest of us kids?

Honestly, I feel like a kid in a candy store pointing to some of the yummiest treats, shouting out to my friends, “Hey look! You wouldn’t believe what I found! Come get a taste of this!”

Of course, this project wouldn’t have come about if a bunch of fans hadn’t written to University of Minnesota Press and asked them to do this book too, so I can’t take the credit for finding this project all on my own.

As for the question about whether this is a literary or artistic project, I suppose I think of it as a little bit of both. It definitely gives us a window into a particular moment in Japan’s literary history, but it is an artistic product as well—filled with interesting and memorable images, curious connections, and all sorts of goodies.

Q: What are some of the things that we might look forward to in the book The Luminous Fairies and Mothra?

This might be a good time to mention that there are are some very big ways in which the novella, which was published in January 1960, differs from the final film that was released in July 1961. Tōhō Studios commissioned the novella, and then once the novella took form, the studio started adapting it to the screen.

Meanwhile, Tōhō published the novella in a popular magazine with a huge circulation, using the novella almost like an advertisement for the forthcoming film.

The thing is that since the novella came first, there are lots and lots of differences between novella and finished film. Some of these had to do with decisions that Tōhō made while planning the film.

One of the most immediately noticeable differences has to do with the fact that in the novella, there are four fairies instead of simply the two we see in the film. I suspect that is because Tōhō Studios had found the perfect actresses for the role of the fairies—the pop duo sensation The Peanuts, which consisted of two identical twin sisters, Emi and Yumi Itō.

However, there are lots of other differences that are not necessarily so practical in nature. The novella contains a long creation story that was cut from the film.

There are extended descriptions of protests in the book that take place in Tokyo after Mothra begins to attack, but the political subtext has been significantly modified by the studio.

The filmmakers have added a mysterious text in an unknown language, as well as some final scenes that craw upon Christian imagery to imply that Mothra is some kind of messianic savior.

I could go on and on about the differences, but I don’t want to spoil the surprises for our readers out there!

Q: Is it even possible for there to be any more of these kinds of literary surprises out there somewhere? It seems hard to imagine what else there would be... but then, I never expected these...

You know, I still have a thing or two up my sleeve. Although I don’t have a publisher lined up yet, I have a dream about doing an anthology of kaiju stories.

Before the 1954 Godzilla came to theaters, Tōhō created a multi-part serial radio drama that was broadcast nationwide to help create an audience for the forthcoming film. I imagine that Tōhō did this because listeners would find themselves curious, wanting to see the giant monster and trying to image how the scenes of destruction might look, thus priming them to come to the theater when the film was released.

Later, the films Rodan and Godzilla vs. Biollante were both based on novellas, so I imagine that if I translated all of these things, they could be a backbone for an exciting kaiju anthology….

Q: Are there other pieces of kaiju literature that are not associated with Tōhō?

After the huge success of the 1954 Godzilla, lots of Japanese writers started writing stories about kaiju, so there are loads of stories, novellas, and full-length novels by authors who had nothing to do with Tōhō whatsoever. I would love to pull together some of those stories, such as those written by the science fiction giant Sakyō Komatsu 小松左京, to include an anthology. Komatsu was as big in Japan as Isaac Asimov was in the United States, so it is crazy to me that such an important, brilliant, and prolific writer has only a handful of translations into English. There is one story in particular that I think is one of the smartest, most surprising kaiju stories I’ve ever read.

After the 2011 earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdown that ravaged northeastern Japan, there was a new wave of kaiju stories. We can see how effective kaiju were as a vehicle to talk about government response and the problems of dealing with massive disasters—nuclear disasters in particular—in the film Shin Godzilla, released in 2016.

Even before this film came out, lots of writers started writing kaiju stories as a vehicle to explore the massive traumas and the nuclear anxieties that enveloped the nation. Again, it would be exciting and important to bring some of these stories into an anthology.

One other particular stand-alone kaiju story that really stands out in my memory is the wonderful, long novel The Rampaging God 『荒神』 by Miyuki Miyabe 宮部みゆき, the author of many first-rate mysteries, adventure stories, and historical novels—some of which have even been bestsellers in English translation.

The Rampaging God was originally serialized in a newspaper in 2013 and 2014 and stretches to 688 pages in the edition I have. It describes the appearance of a kaiju in the early eighteenth century, and so it is rich with historical detail, which Miyabe filters through her brilliant awareness of human nature.

I’d love to get the chance to translate this book, but at 688 pages in the original Japanese, it would be a kaiju-sized undertaking!

In short, only the tiniest tip of all the kaiju literature that exists in Japanese has been translated into English. There is a lot of work to be done in this field! What an exciting time to be a scholar, translator, and kaiju fan!

Find more Jeffrey Angles online

Interview: Jeffrey Angles about translating Godzilla and Godzilla Raids Again (Toho Kingdom)

Japan’s most famous ghost story | Jeffrey Angles | TED-Ed

“Get to know the Japanese legend of Hōichi the earless, a monk summoned by a mysterious samurai to perform songs of past battles.”

Growing Up With Godzilla Ep. 92 | Sympathizing with Monsters | with Dr. Jeffrey Angles

“Iconic translator, Japanese literature scholar, and professor Dr. Jeffrey Angles joins me to discuss windows into cultural history and sympathizing with monsters. We also discuss the forthcoming translation of THE LUMINOUS FAIRIES AND MOTHRA.”

More from Monster Complex®

Godzilla: Surprising facts—like when the Japanese studio said “That’s not Godzilla”

Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur: 13 Facts Behind the Disney+ Series

Godzilla vs American version ‘Zilla’ (Hollywood’s 1998 version)

How All 3 Cloverfield Films Are Connected (And wait—what about the 4th movie?)

Johnny Sokko and Giant Robo—Theme Song, The History, and The Giant Monsters

Toho vs. Marvel for ‘Godzilla Destroys the Marvel Universe’ comic book event

Exploring the endless impact of 1970s show Kolchak: The Night Stalker, with several videos discussing the show’s triumphs. Plus info about all the new books coming out this year!